Project presentation

“When I look back, I have no doubt : the most important things I accomplished were neither climbing mountains nor my trips to the ends of the globe. What is really close to my heart is to have allowed the construction and ensured the daily life of schools and clinics for the dear friends I have in the Himalayas.”

Edmund HILLARY, first alpinist at the top of Mount Everest

A bit of history…

The nepalese normal route

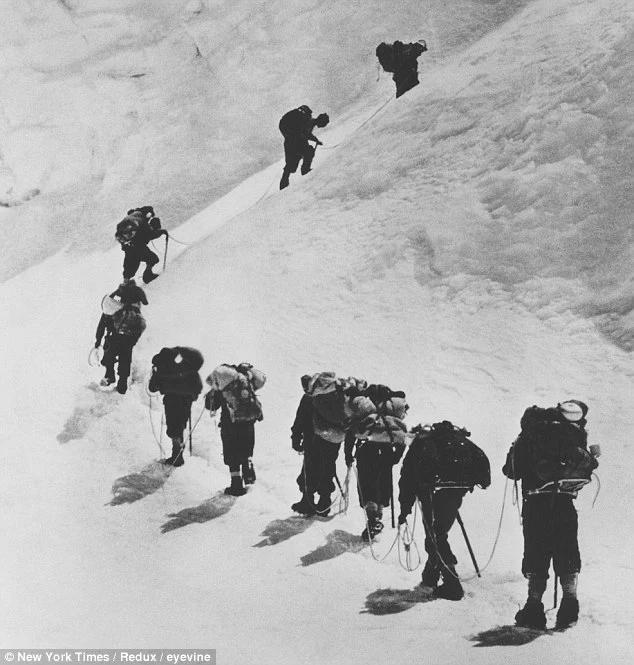

This is the route climbed by E. Hillary and S. Tenzing back in 1953 to be the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest. It followed the opening of the mountain to foreigners. And it is still today the most used route, despite great objective dangers and suffocating attendance.

This international openness makes it possible to develop the region, and the climbing permits finance public actions in one of the poorest country of Asia. Today, tourism is the main source of income in this very steep and difficult to access region.

The waste

Of course, this mass tourism brings a lot of waste and, for this reason, many expeditions have been formed to clean the roof of the world. Unfortunately, they generally only consist in take a part of the waste a little lower. Some materials are well valued, such as metals or certain gas cartridges, for example, but too much plastic ends up in open landfills or, worse, in rivers. These plastics then follow their path, polluting the Nepalese valleys and other adjoining countries before flowing into the ocean. There was an incinerator in Namche Bazar but it was damaged by the 2015 earthquake and was anyway undersized to process all this waste.

To learn more about the waste processing in the world, we wrote an article on the subject.

The Khumbu

The Everest region is called Khumbu. It is very remote and has no road access. Porters and Sherpas must therefore carry all the equipment on the their backs and on yaks.

The largest city in the region is called Namche Bazaar, located at 3,500 meters above sea level. Most treks reach it from the town of Lukla which is the last town accessible by plane, at 2,800 m. Then, the treks often go to the Everest basecamp at 5,300 m located about thirty kilometers away.

Given that the local population‘s main concern is to eat their fill, we imagine that it is difficult to envisage a 50 km walk through the mountains to bring its waste and that of tourists back down to civilization… And yet this desire is present as shown by the actions already implemented and their enthusiasm for our project.

Tri’Haut pour l’Everest…

Everest Green

It all started in 2018, at the Ciné-Montagne festival in Grenoble, when the screening of the documentary Everest Green, by Jean-Michel Jorda, gave a concrete idea of project to our adventurers, already aware of the pollution issues in the mountains.

Then followed an initial contact with the director of the moovie and with many actors of the high moutains in the Himalayas. The message is clear on both sides : THERE IS AN EMERGENCY !

Many are the expeditions aiming to clean up the peaks subject to mass tourism. These are beautiful collective actions, where waste are often lowered down to the valleys. But Nepal does not have the means of treating it.

Jean-Michel Jorda then put us in contact with trustful locals who have for ambitious goal to install an infrastructure to process waste in the Everest region.

Pangboche

At two-day walk from Namche Bazaar is Pangboche, surrounded by high mountains. The last village inhabited year-round before Everest Base Camp has hosted a small dump near Dudh Koshi, the milky river, for several years. As confirmed to us by the inhabitants and in view of our observations on the spot, it is a strategic place because it is located halfway between the various lodges and high altitude base camps, and the other towns and villages of the valley, making it an excellent collection point.

It is also the village where Henry Sigayret, the mountaineer nicknamed Sherpasig, settled 40 years ago after leaving his Western life to settle there with his new Sherpa family. It allowed the inhabitants to gain access to electricity before many other villages located further down the valley. Thanks to his work, the inhabitants are very involved in the life of the village and a local association manages the installations in an autonomous way. They are also very motivated to deal with the waste problem by helping us to set up an infrastructure and ensuring its operation and maintenance after that.

A first idea – the incinerator

After discussing with the locals, they suggested us the installation of an incinerator, which then seemed to be the most suitable solution for this region. This “recycling” solution makes it possible to process all plastics without worrying too much about their type, and the addition of filters and heat recovery systems makes it possible to considerably limit its impact on the environment while providing a reliable source of heat or electricity to the inhabitants.

This is why we learned much about this technology and worked with our technical partners for nearly 6 months in order to imagine a low-tech installation adapted to the region…

But our reflections led us to doubt the viability of this solution for this specific region where transport is mainly done on foot. Indeed, such an incinerator would have consumed too much fuel, which could not have been assumed by local organizations, and which would not have been profitable for them. It is also for this reason that the old incinerator of Namche Bazar has not been put back into service… We therefore had to find something else !

Still, we would like to thank the various actors who helped us with the study of the incinerator :

- Our school, the ENSE3 with its labs and teaching staff;

- The members of the Falchen Kangri project who installed an incinerator in the Himalayas 20 years ago with the INSA Lyon (thermal study, execution plans and feedback);

- A company specializing in incineration furnaces.

A second idea – plastic pyrolysis

The incinerator’s decision represented a real turning point in the project, as we had to find another solution: is it possible to recycle waste in a different way than by burning it to obtain heat or electricity?

After exploring several avenues and reviewing all existing waste recycling solutions, plastic pyrolysis seemed the most appropriate for Khumbu.

But what is pyrolysis? Pyrolysis is an oxygen-free combustion process that converts plastic into fuel oil and gas. As fuel oil is extremely expensive in this region (which is one of the reasons why we questioned the incinerator), it was interesting to be able to produce it.

Pyrolysis has many advantages over incineration:

- low-tech system, easier to install and maintain

- lower combustion temperatures, reducing the toxicity of fumes and thus their treatment

- waste valorization, providing an argument for the operation of the plant for the local population

- lower proportion of post-combustion residues, which can be easily treated as they are not considered “hazardous waste”.

So why not turn directly to this process?

In reality, this technology is little known, due to the difficulty of implementing it on an industrial scale. The system has to be adapted to the type of waste being processed, in order to obtain satisfactory oil and gas quality.

But the system does have its limitations, not least the fact that it doesn’t work with all types of plastic. While it works well with PP plastics (packaging), it does not work well with PET (bottles), which is also present in large quantities.

A first prototype was produced by the 2021 team, but after extensive studies on the machine, we had to stop its design in 2023. To find out more, we invite you to read the following article: Pyrolysis.

Our solution:

The aim is to build a waste management center equipped with machines for sorting and recycling waste in Pangboche. It integrates the waste management plan of the local body, the SPCC:

Nepalese organizations

For its sustainability, it is essential in this project, which is on our initiative, that the local populations take ownership of it.

The Khumbi Illa Foundation, through Namgyal Sherpa, allows us to get in touch with two important local organizations :

- SPCC (Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee), the organization in charge of waste management in the region.

- NMA (Nepal Mountaineering Association), a non-profit association whose main objective is the protection of the Nepalese mountain environment.

These two important Nepal institutions in the expedition management will be able to redirect the waste generated by the latter to our installation.

For the logistics and maintenance parts, we are accompanied by the region’s president, Laxman Adhakari as well as the Youth Club of Pangboche association.

Jean-Michel and Henri also put us in contact with locals sensitive to this issue. This will make it possible to take care of the waste produced in the surrounding villages. The trust of the inhabitants towards Henri and his family will allow us to benefit from assistance in carrying out the work when we are on site and above all to make the installation permanent.

We insist on the proximity with Nepalese organizations and local actors, in order to don’t make the mistake of carrying out a project with our Western vision without taking their opinion into account (see They support us).

The first phase of the project in the fall of 2021 therefore made it possible to meet the local actors and our contacts there to reflect, with them, on an action plan that suits everyone (see 2021 – Project launch).

Awareness and communication

Because the best way of treating waste is to not produce them, we think it is important to talk about the problem and encourage tourists, and locals, to reduce the amount of waste they generate.

And this happens at all stages of the project :

- Before we come to Nepal, we communicate on this problem through our social networks and the medias (radio, press, television…).

- When we will be in Nepal, we will be able to meet directly the tourists and the locals in order to explain the problem, our project and encourage them to reduce the amount of waste they generate. We will also encourage tourists to bring back with them hazardous waste (batteries…) because these waste end up in landfill since no infrastructure exists to treat it in the entire Nepal.

- Finally, once we’ll be returned from Nepal, we will continue to communicate on our project and on the importance of reducing our waste quantities, throughout conferences and interventions in schools/colleges/high schools for example.

In order to increase the impact of this awareness, we also think it is important that we are supported by influential people. This is why we are working to make contact with as many people as possible.

Follow us on our social medias

The sporting and scientific project…

Mera Peak and Ama Dablam

During this adventure, we will also discover the peaks and their glaciers above Pangboche.

Our sporting objectives are the realization of a trek of several days in the Khumbu and the ascent of an high altitude summit. The Mera Peak, with its 6,476 meters, lends itself well to our expectations since it is an accessible summit which does not required much mountain experience.

In addition, CNRS scientists visit its glacier every year to follow its evolution. We would like to help them in this measurement campaign.

In addition to the Mera Peak, Martin and Nathan will try to climb the Ama Dablam (6,812 m), a mythical summit above Pangboche, but much more technical.

Scientific observatory

The Mera Peak, in addition to being very accessible for a first experience in high altitude, is the place of experimentation of an international program led by the CNRS. Indeed, it is up there that Grenoble scientists from the IGE (Institute of Environmental Geosciences) meet every autumn to take measurements on the glacier at more than 6,000 m.

Mass balance, ablation and other bamboo-based measures… it’s all there. The goal is to see the past but also future evolution of these immense water reservoirs, the risks and the advantages they represent for the populations, and how their evolutions are witnesses of the climate change in the highest region of the world.

The Lobuche pyramid, built with heavy materials mounted on men’s back and yaks, which contrasts with the traditional habitat of the Nepalese Khumbu, is in fact the base camp for the CNRS scientists.

To learn more about glaciers, how they work and what are the stakes in relation with them, see our article on the subject.

What’s next ?

For us, this is a multi-year project. And it needs to be shared to make it easier to set up similar projects in the future. That’s why we’re using the images we’ve acquired on site to make a short documentary about our project. We’ll be using this material, along with our on-site experience, to give talks on our return. This is all part of the awareness-raising aspect of the project, which is just as essential as the project itself.

We believe that a fourth team will be needed to raise awareness among local people and help them take control of the machines, so as to make the project as sustainable as possible.